In a discussion on a medical website of rejuvenation research, I found one pretty good comment amidst the Pharma-haters, so I wrote this (edited here for clarity).

|

In a discussion on a medical website of rejuvenation research, I found one pretty good comment amidst the Pharma-haters, so I wrote this (edited here for clarity).

|

The primary volitional choice is to take charge of your mind or not—i.e., to focus or not. “Focusing your mind” is a broad abstraction; what are the basic acts you use when you are in focus?

To change the metaphor, the primary choice is to manage the operations of your mind or not. What are the basic tools of mental self-management?

It is clear that one basic volitional operation is directing your mind: enacting your purpose by giving attention to this or that. If the primary choice is to direct your attention at all, rather than letting go and letting what passes through your mind be determined by chance, short-range factors, this basic subchoice is taking the wheel and steering.

As I’ve discussed, “steering” involves the choice to either keep in focal awareness one or more of the items that are already in focal awareness, or to bring into focal awareness material of which one is less clearly or only dimly aware—things on the periphery of awareness. Further, the conceptual level gives man the possibility of actively seeking material that was completely out of awareness, being neither focal nor peripheral, through the use of words, concepts, propositions and reasons of which one is aware. Thus, I can order myself to think of animals in a zoo or how to play a C chord on a guitar or whether or not I should stop working now—none of which were in even the periphery of my awareness a minute ago.

But the choice of what to attend to presupposes the primary choice: to take charge of the operations of my mind, pursue a purpose, and work to attain full awareness of reality.

So, riding with a stray thought, apropos of nothing, just because it feels good to do so is not to make a choice at all, neither to focus nor to direct the object of one’s attention.

The choice of subject, of what to attend to, is something that I and others have “chewed” for many years. But a couple of days ago, I thought of another basic operation of consciousness that’s under direct, immediate volitional control: scope.

If the choice of subject is the choice of where to point the searchlight of your mind, the choice of scope is the choice of how broad or narrowly focused is that light.

You have the power to “zoom in” and to “pan back”—to narrow the beam to give more attention to a part or aspect of a subject or to widen the beam to get a wider, integrative view. When one pans back, the illumination per square inch (so to speak) drops, which causes particulars and details to be dropped, but the surrounding material is now given some attention.

Think of a map on your smartphone. For a given screen that is displayed, you can move north east south or west. But you can also spread your fingers on the screen, to get a closer view, or pinch your fingers on the screen to pan back and see more territory at once. And, as I’ve mentioned, moving in closer reveals more details or specifics; but pinching to get the larger-scale view brings the wider context into view.

The ability to control the scope of your attention in this way is crucial for your general sense of self-control. Indeed, it’s crucial to your experiencing your self, itself. And in terms of cognition, your control of the scope of your attention is a big factor in explaining the difference between examination and mere gazing.

An animal gazes at things, looks at things, but does not examine them. A human being, from early infancy, can use the ability to zoom in on an object to consider the basic question of all thought: What is it?

To answer that question, one has to both analyze and integrate—i.e., both zoom in to perceive parts (and, for an adult, to consider aspects) and to pan back to observe how the item relates to the wider context, how it fits into (or contradicts) the network of one’s knowledge.

In the Objectivist literature on free will, the point is emphasized that the choice of subject is not a primary: it depends upon one’s knowledge, interests, circumstances, and psycho-epistemology. The same is true of the choice of scope: whether one zooms in or pans back (or neither) depends on, but is not deterministically set by, the same factors. We are all familiar with this in detective shows. The detective notices some apparently innocuous detail that has been in the field of view of everyone, but given attention by none. But the reason the detective can choose to zoom in on it is that he has a background of knowledge and values. He would have had no purpose in doing so when he was two years old. Lacking the motivation, he could not have focused on it (except by wild chance) and even if he did — even if someone else showed the clue to him and asked him to think about it — he could have made nothing of it.

Adjusting the scope of one’s attention to match the requirements of gaining full awareness is a basic subchoice that one makes if one is in focus, pursuing knowledge, striving to deal with reality.

I have been promising a book on Free Will for about a year, maybe more, so I think in good conscience I should give a progress report.

I haven’t yet decided whether the book will be on the free will—determinism debate (and thus be largely polemical) or will be a positive book explaining free will to the minds ready to seize the idea and improve their own lives.

If it’s the first, the title that seems to me the best marketing copy is:

If it’s the second, I have several leading candidates:

(I favor the first of these.)

But more interesting, I think, is that I found a way to make the writing more pleasant. In fact downright enjoyable. I’m casting it, mainly or wholly, as a dialogue. (Which means I’m leaning to the polemical book.)

I have two characters, a man and a woman. They are identified only as “He” and “She.” The woman is the one with all the right answers. The man is well intentioned but has absorbed all the bromides of the culture. But he is refreshingly honest.

There’s an overlay of potential romance coloring their discussion. I’ll give you the opening “set up”:

He liked talking with her.

She never failed to startle him with a fresh perspective that challenged his comfortable assumptions. On so many topics, she would crush the safely conventional slogans he would float out. He liked that.

She cut through his verbiage. She gave no quarter, brooked no compromise. “If it’s wrong, it’s wrong,” she would always say. He liked that.

It didn’t hurt that while delivering the thrust home, she would show a slight smile, as if they were co-conspirators in some subversive scheme. Which, in a way, they were.

They had no agenda, but no matter what sparked the discussion, things always seemed to go back to the deepest questions—to philosophy. Today, a discussion beginning with the issue of Affirmative Action moved quickly to the issue of individualism vs. collectivism, and from there to one of the deepest and most consequential of all topics: free will.

Sadly, I voted for Trump for President. I panicked over the idea of the Dems packing the Supreme Court, which Biden pointedly wouldn’t deny they’d do.

But after January 6th, I rescinded my vote. Which of course is impossible. But I did it “in software.”

Sometime later, I followed up by changing my voter registration from “Republican” to “Independent.”

Now, after the anti-Roe v. Wade decision, I don’t even want the Republicans to win the Senate. And it looks like the Republicans have snatched defeat from the jaws of victory by this Supreme Court decision. It will definitely lessen, and maybe eliminate, their gains in the mid-term election.

(I know, the Supreme Court is not an organ of the Republican Party; the Justices have to rule as they think right. But Trump nominated judges who were expected to deny a woman’s right to her life.)

Trump is a traitor, and a very cheap one at that. In order to fan a ridiculous hope of staying in power, despite the election, he announced on election eve, that he knew, using his super-powers, that there had been fraud—enough fraud to make him the actual winner. God gave him a mystical vision of what really happened in all the key election headquarters in five states. He didn’t have to wait for any court determinations: he knew then and there what had happened.

He knew because he felt it.

He felt really strongly, in the deepest chambers of his heart, that the majority of American voters wanted him. They loved him. They were wearing his MAGA hat. They didn’t care what he did or said, they loved him for himself. James Taggart could only envy Trump’s effusion “I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters.” [https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/donald-trump-fifth-avenue-comment/]

Therefore, when the vote tallies didn’t bear that out, it was proof, PROOF, that the tallies were rigged. A simple syllogism.

With an equally ardent mysticism, he announced repeatedly that despite the vote, he would be the President come inauguration day. And that’s why Jan. 6 happened. And that’s why he’s responsible for the assault on the Capitol by creatures from the age of Vandals and Visigoths.

Had he said that he accepts the people’s vote, that he follows the rule of law and the peaceful transfer of power, then there would have been no barbarian storming of the gates. Several people who died would still be alive. The Republican Party might have been a supportable party of opposition.

But Trump continued his ongoing war against reality, and now we are at the point that Ayn Rand warned us about when the protagonist was not a demented thug but that gentlemanly, soft-talking, avuncular figure, Ronald Reagan:

The kind of Halloween-like creatures who are trying to take over today’s intellectual arena were not created by the Reagan Administration; they exist in any period, in the dark, unventilated corners of history. But in the periods of philosophical default, they come crawling out into the full, open moonlight. Today they are organized under many pretentious names and slogans. The most presumptuous of the names is the “Moral Majority,” and the falsest of the slogans is the claim that they are “pro-life.” What all these people have in common is that they are militant mystics who have learned to be arrogant by encountering no opposition. Their common ideal, the unacknowledged embodiment of their political goals, is the man who has succeeded in uniting religion with politics and establishing a religious dictatorship; he is known as Ayatollah Khomeini.

No, the Reagan administration did not create those militant creeps—but it sponsors and supports them to an embarrassing extent. Mr. Reagan has been declaring that he agrees with some of their ugliest demands, such as the anti-abortion issue and the “creationism” issue. It is embarrassing to hear a president of the United States endorse the plain, crude, illiterate superstitions of the populace of the Middle Ages. [“The Age of Mediocrity,” Ford Hall Forum, April 26, 1981; reprinted in The Objectivist Forum, June 1981.]

The concrete occasion for writing this post is the FBI raid on Trump’s home at Mar-a-Lago. Fox and Friends were outraged. Trump supporters assume that this is an attempt by a politicized FBI to keep Trump at bay, and prevent him from running in 2024.

Yet that theory is as nonsensical as its leftist counterpart. Remember when the Left was screaming that Bush knew all along that there were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq? “He lied! He lied!”

But if he had known, why would he have launched a mission that would find nothing? Why would he set up a massive military effort that would show him to have been colossally wrong?

I asked a Leftist that, and he literally screamed at me, “Because he’s a MORON!”

Now, the Right is saying that the FBI raided Mar-a-Lago knowing that there was nothing of importance there to get in the raid—or at least without a solid reason to think they would find “documents of mass insurrection” or whatever.

But—entirely predictably—this has drastically improved Trump’s position. Why would the Left want to energize Trump’s base and undertake another failed attempt to discredit him (like the Christopher Steele fiasco)? I know . . . Because they’re MORONS!

No, you don’t do something as dramatic and theatrical and unprecedented to a man almost half the country already regards as a victim of governmental misconduct unless you either have to or you know what you are going to find.

(By the way, the denizens of Fox and Friends made the argument that “He was already cooperating with them,” because “He had already turned over many documents.” Yes, all the documents that are neither important nor incriminating. If he were holding back materials, that would have made the raid necessary. At least that’s the claim I’ve heard from the other side, and it’s the obvious claim that would have to be rebutted if you’re are going to say, “He was cooperating.”)

Lifespan is one of the very, very few books that can be life-changing.

It is a report on the exciting developments in eliminating—and reversing—aging. And it’s written by one of the pioneers in the field, David Sinclair of Harvard and MIT.

Sinclair’s credentials are staggering. Here’s just part of them, from the book’s end matter:

a tenured professor of genetics, Blavatnik Institute, Harvard Medical School; co-director of the Paul F. Glenn Center for the Biology of Aging Research at Harvard; co-joint professor and head of the Aging Labs at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia; and an honorary professor at the University of Sydney. . . . He has published more than 170 scientific papers, is a coinventor on more than 50 patents, and has cofounded 14 biotechnology companies in the areas of aging, vaccines, diabetes, fertility, cancer, and biodefense.

This book was written in 2019, so it is fairly up to date. Its message is: age-reversal and hundreds of years added on to your lifespan is coming, it’s unstoppable, and it will be here soon.

Although he doesn’t stress it, the barriers are political not scientific or technological. Every nation in the world has an FDA-type government body devoted to stopping medical progress. As I understand it, in no country on earth can a researcher even inject himself with his own creation.

But there are loopholes and ways through the briar patch of controls. One such is to get an age-fighting or age-reversing substance approved as a treatment for one particular disease, say diabetes, and then use it “off label” as a general remedy.

Sinclair’s conclusion:

It’s also hard to know what I know, to see what I’ve seen—the results of experiments and other clinical trials around the world years before the rest of the world learns about them—and not believe that something profound is about to happen to humanity.

The value of this book is its evidence that we will get young again and its explanation of how and why. You’ll learn about “longevity genes,” animals that already live centuries, why aging is a (curable) disease not “just man’s fate,” the role of the “epigenome,” vigor-enhancing lifestyle changes you can make now, and good food supplements to take now (nothing weird).

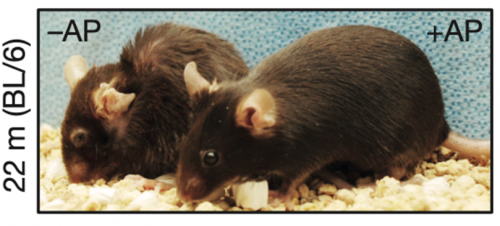

I know you’re still skeptical, to put it mildly. So here is visual evidence:

The mice, as I understand it, are the same chronological age, but look how much younger the one on the right looks. Compare the hair on their backs, and their eyes.

I’m not sure if this particular mouse had looked older (like the one on the right) and then was de-aged, or it just has aged much more slowly. That’s an important distinction for some of us who are already the mouse on the left. But other studies with other treatments have shown mice de-aging.

Mice are mammals, like us. They are actually very good representatives of human biochemistry and physiology. And we’re talking about something fundamental, something having to do with how DNA works, not anything pertaining to how mice differ from men.

That picture is not from the book, but here’s a passage that is:

“David, we’ve got a problem,” a postdoctoral researcher name Michael Bonkowski told me one morning in the fall of 2017 when I arrived at the lab. . . . “The mice,” Bonkowski said, “They won’t stop running.”

The mice he was talking about were 20 months old. That’s roughly the equivalent of a 65-year-old human. We had been feeding them a molecule to boost the levels of NAD, which we believed would increase the activity of sirtuins. If the mice were developing a running addiction that would be a very good sign.

“But how can that be a problem?” I said. “That’s great news!”

“Well,” he said, “it would be if not for the fact that they’ve broken our treadmill.”

As it turned out, the treadmill tracking program had been set up to record a mouse running for only up to three kilometers. Once the old mice got to that point, the treadmill shut down. “We’re going to have to start the experiment again, Bonkowski said.

It took a few moments for that to sink in.

A thousand meters is a good, long run for a mouse. Two thousand meters—five times around a standard running track—would be a substantial run for a young mouse. . . . Yet these elderly mice were running ultramarathons.

The book has 50 pages of footnotes. I would skip Part III entirely—it’s on social political implications and he brings in his own political ideology, which is badly mixed (to put it optimistically).

There’s a co-writer, who’s a journalist and writer, not a scientist. The result is a very readable book.

| A symptom of the almost universal misunderstanding of inflation is the belief that people are unable to pay the inflated prices or at least are unhappy about paying them. They aren’t.

(I’m not talking now about that minor part of the price rises that are due to lessened production; that is a completely different matter—and is not inflation. The great bulk of today’s price rises are due to the government flooding the market with phony dollars—which is exactly what inflation is.) As a first approximation, the general price level is determined by the ratio of the money supply to the volume of goods offered for sale—including services under “goods.” For simplicity, take services to be included under “goods.”) (It’s a first approximation because the actual causal factor is people’s expectations about the future ratio, but the main thing shaping those expectations is the current ratio.) Changes in the denominator of that ratio—i.e., changes in the quantity of goods offered for sale—are determined by factual conditions, such as the state of technology and whether or not there’s a war . . . or a pandemic. But things are fundamentally different in regard to changes in the numerator—i.e., changes in the quantity of fiat money. That’s based on the subjective, politically motivated rulings of government officials. Incidentally, changes in the gold supply are in the category of objective phenomena, not politically dictated ones. So, in a gold-based system, changes in the gold supply cannot be taken as inflation or deflation. Inflation is a government-created phenomenon by definition—i.e., by its fundamental difference from any objective, economically-governed occurrence. For ease of communication with the public, I use the phrase “price inflation” to talk about the upward change in the general price level and “monetary inflation” to refer to inflation by a proper definition. Then the point can be formulated as: monetary inflation causes price inflation. That causal identification remains true despite the fact that a decline in production also causes price inflation. Here, “causes” means: “is one causal factor in creating.” One causal factor can counteract another. And that has been the story, I believe, for the last 20 years: technology’s expansion of production has kept pace with the government’s expansion of the fiat money. The result has been: little price inflation—but with several other bad consequences, including a lower rate of progress. Recently, however, the harm done by trillions showered down as “Covid relief” plus the decline in output due to shutdowns have overwhelmed technology’s advance. Despite the shutdown’s interruption of production, the main cause of price inflation today is government’s monetary expansion. The money supply has maybe doubled (it’s nearly impossible to find any exact data), and the decline in production has been bad but not that bad. Remember, the U.S. government sent out thousands in the mail to virtually everyone. Plus there’s the Fed’s expansion through the banking system—which has been required to keep interest rates near zero for years and years. So, if you are willing to grant that this price inflation is essentially due to monetary inflation, I can go on to make good on my opening point: high prices are high because people are happy to pay them. Yes, of course, they would prefer to pay less, but the price at which any good is actually sold is the price someone is happy to pay. Yes, happy: the buyer is gaining a value. At the higher price, he would prefer to have the good rather than keep his dollars. That’s why anyone buys anything. In his judgment, paying the price will increase his well-being. It will make him better off. He’s glad to pay it. The customer’s desire to pay is what pushes prices up. It is claimed that sometimes costs push prices up. But that is wrong in two ways: 1) a cost is a price, so it can be pushed up only by the demand of the buyers—i.e., demand of the businesses who want to pay that cost, 2) the people who are paid the higher costs get more money per unit, so they can bid up prices for the final products. For instance, there’s a labor shortage, so wages and salaries are going up. But they don’t go up unless the employer knows that he can pay more—i.e., he must expect to get more sales revenue, due to price inflation. And when wages go up, the employees receiving the extra funds spend them mostly on consumer goods. So in most cases, the employers will indeed be able to sell at higher prices and get higher sales revenue. The whole change in prices is an adjustment of prices throughout the economy to the monetary expansion. It is not a change in the average person’s (short-term) well-being. Psychologically, it seems like one is worse off when price inflation hits, because one has not adjusted to, say, $5-per-gallon gasoline. But the main reason gas is at that level is that people are bidding it up that high with the newly printed dollars they have been given by the government. And consider: $5 per gallon is 5 times the price it was in 2002 (in Austin, TX). But the gold price today is 6 times higher than it was then. So, if you paid in gold, you would be getting more gas for your money today than in 2002. And much more than in 1962 (gold being 45 times higher). The gold-price of gas continues to fall. The essential problem with monetary inflation is not rising prices. One essential problem is the forced sacrifice of some to others: those who don’t get or don’t spend the new money until later are sacrificed to those who get and spend it first. The other essential problem is inflation’s distortion of production. Inflation wrecks the plans of borrowers and lenders, especially the plans of those who borrowed to finance businesses. The Austrian economists are right: inflation creates malinvestment. Inflation works by faking the cost of capital. By fooling people into thinking more factors of production are available than actually are, lots of never-to-be-profitable projects get undertaken, and there will have to be an eventual liquidation of the malinvestment. (This can be a rolling re-adjustment or a sudden crash.) A fascinating issue here is the decisive role of inflation-expectations. The so-called “velocity of money” is actually the influence of anticipated inflation. If the rate of monetary inflation were (impossibly) known with certainty for 100 years in advance, all market prices would reflect the anticipated effects and the adjustment would occur smoothly and painlessly. But then the monetary expansion would not have the effect the statists “planners” want it to have. To achieve its “stimulus” effect, the inflation has to surprise people, including bankers, financiers, traders—everyone. To “stimulate,” the government has to trick people, fool them, defraud them. For example, if you’re a lender, you expect the money you lend to be worth a certain amount when it’s repaid. Your inflation-expectations guide your decisions. For the government to stimulate the economy, to call forth extra loans and extra investment, it has to fool the lenders and investors into thinking they have more real funds (as opposed to paper funds) than they do. They have to trick the lenders and investors into thinking the real value of their future return will be more than it actually will be. Suppose you have $100 to lend. If you anticipate a 2% rate of inflation, then if you expect an investment to earn a risk-discounted 6%, you subtract that 2% and figure the nominal 6% is only a 4% real return. How does the government get you to lend more? By sending you $1,000 in the mail. Now, if you don’t realize that the money is being depreciated by that act, then you are willing to invest, say, $100 out of that $1,000 if you can get a nominal 6% return. Well, maybe not 6% this time, because those high-return projects are already funded and also because you are not the only one with extra savings, thanks to the government’s check-mailing program. So you lend another $100 at 5.5%, let’s say. That’s still okay with you, as long as you expect the value of the money to depreciate only 2%. But due to the check-mailing program, the value of the money depreciates more. Maybe 4%, maybe 8%. Suddenly you find that both of your loans have lost you money. If the cost of living has gone up 8% (as it has recently), your first $100 got you a 2% loss, and your second got you a 2.5% loss. At that point, if they are concrete-bound, lenders subtract 8% from the nominal amount of dollars they will be repaid, and that means fewer loans, and that in turn means the bust cycle begins. (I say, “concrete-bound,” because they are just reacting to the past concrete rather than realizing that the government will inflate at a higher rate to trick them into maintaining the false boom. Savvy traders know that 8% is yesterday’s rate, and that to avoid a recession, it’s likely that the government will inflate at much more than 8%. How much more, they can only guess.) One wealth-protection strategy is to put money that would be going into productive ventures into “hard” assets such as real estate and gold. In the early stages of the price inflation, the stock market is a good bet, but in the later stages, when the chaos hits and businesses can’t plan, only hard assets preserve real value. But before you rush to buy gold or make any other investment decision, remember Ludwig von Mises’ dictum: in order to make a higher-than-average rate of profit, you must know something that the market does not. And I think “the market” here means: the major players in the market, those whose decisions control the most funds—the Warren Buffets, the Blackrock Capitals, the Citibanks, the big hedge funds.) To return to where we began, I hope it is now clear how superficial and silly is the oft-heard complaint: “The price of things has gotten to where people can’t buy them.” Prices are that high because people are buying them at that price. That’s the price things have been bid up to. Give people more paper dollars and they are going to spend them. |

A member gave voice to the way I used to think of it, until about 15 years ago:

In a civilized society, the use of force is banned except in emergency self-defense. In other words, gun ownership requires justification. Actions that do not involve force, such as crossing the border or using drugs, do not need justification, but acquiring a weapon does. One needs a reason to seek the means of killing people. And there is a justification: self-defense.

But one can’t say, “I just want to amass weapons and it’s none of anyone’s business.”

Then I came to view it more procedurally, so that I now think the issue is one of preventive vs. proper law.

Here’s the procedural issue. Congress or regulatory agencies should not be debating over and making lists of controlled vs. uncontrolled substances and objects. Not even for bioweapons. That is not the way to write law. Every time a new substance is synthesized, should its inventor have to get clearance from every state and the federal government?

Rather, it is illegal to injure someone or damage his property. And it is illegal to threaten damage, i.e., to give any man objective reason to fear that damage may be coming to him.

The burden of proof is on the person claiming that someone’s purchases and/or activities pose an objective threat. But all of the cases people are worried about meet that test. E.g., some random citizen wants to store dynamite in his basement (which adjoins yours), someone buys a bioweapon, an 18-year-old boy buys an AR-15 and a lot of ammo for it. Those things would scare anyone. And the police can intervene without there being some law against those concretes.

The principle I’ve come to accept is that you don’t illegalize objects, you illegalize acts.

If I walk a rabid pit-bull on a thin leash on the city sidewalk, I’m properly going to be stopped by the police (if it comes to their attention). But to get this result, you don’t need laws against walking rabid pit bulls or regulations relating the weight of the dog walked to the strength of the leash used, you just have law about being responsible for harm caused by an animal you own.

The only counter-argument that I can think of is the idea that we can prevent crimes or prevent mass killings by outlawing certain objects. Specifically, that argument would be: even if the police would act when they saw what was happening, that’s too little too late: let’s stop these weapons from ever getting into the hands of a potential spree killer.

My answer is two-fold:

One consequence of all these Prohibitions is the funding of criminals; they get to make huge profits by supplying the banned substance.

Here’s a novel suggestion. Assume that a certain object really shouldn’t be sold to a certain kind of buyer. E.g., assume that the regulations you want to write would have illegalized selling the AR-15 used in Uvalde to the shooter, Ramos. Assume that the wrongness of this 18-year-old boy getting such a weapon is obvious. Okay, then the parents could sue the gun dealer who sold it to Ramos.

Don’t illegalize the object. Don’t even illegalize the sale of the gun to a kid. Just let the seller know that he will be held liable for any wrongful use of the weapon.

That arrangement enlists the seller’s mind on the side of man’s well-being.

P.S. Subsequent discussion in the HBL Members Forum made me realize that my wording of the proposal left it open to imposing “strict liability.” I should have said: “Just let the seller know that he will be held liable for any wrongful use of the weapon, provided it is shown in court that he was negligent to have made that sale.

This is a column I wrote for Forbes.com in 2013

In Praise of Gold

Keynes sneered at it. Preachers damn it. Bitcoin dreams of transcending it. But free men inevitably choose it. Gold.

Whenever men have had a free, uncoerced choice of the medium of exchange, gold has won the competition, along with its sister element, silver.

Why? Only in recent times has gold had any utilitarian value. The Ancient Egyptians couldn’t use it in computers, but they prized it nonetheless, as did the faraway Aztecs and the Chinese. Men in every place and time have valued gold.

Why? Of what use is gold? You can’t eat it.

No, and you can’t eat a Rembrandt, either. A Chopin Ballade is not something you can eat, drink, or ride in.

It may surprise the spiritualists who damn gold to hear this, but gold, like music and painting, is a spiritual value. Gold is a value because it is radiantly beautiful. It is the esthetic pleasure gold brings that makes men esteem it.

Other of gold’s inherent attributes fit it to be the money commodity, but let’s pause to answer the great unanswered question: what is beauty?

Beauty is intelligibility—a sensory-level version of intellectual intelligibility. What looks beautiful or sounds beautiful is what features an intelligible pattern formed out of pure, simple elements.

Why the pleasure in pattern-recognition? Men’s lives depend upon their minds. The essential mental work that is required is integration: finding the one in the many, the theme behind the variations, the principle behind the concretes. But transforming a bewildering plurality into a clearly understood unity often means going through a difficult, doubt-ridden process. So, there is a definite delight in the easy, doubt-free microcosm provided by sensory pattern-recognition.

I’m generalizing here from what Ayn Rand wrote about why music moves us emotionally:

“Music offers man the singular opportunity to reenact, on the adult level, the primary process of his method of cognition: the automatic integration of sense data into an intelligible, meaningful entity. To a conceptual consciousness, it is a unique form of rest and reward.”

Beauty has been called “unity in variety.” The beautiful is that which features clear elements made into a clear, consistent whole.

The clear elements can be pure musical tones, or it can be shining pieces of gold. The pattern is supplied by fashioning musical tones into a melody or pieces of gold into jewelry, or into gold leaf to make the pattern it coats glisten. Gold nuggets are only the means; the end is a lustrous, intelligible esthetic object.

The other aspect of gold is its unique purity—purity both in its color and in its incorruptibility. In a world that features decay along with growth, degeneration along with too-rare improvement, gold’s imperishable, radiant luster offers the experience of purity, of unfailing reliability, and of stainless consistency. Gold remains gold; it does not tarnish or rust.

Thus, gold is not “a barbarous relic” (Keynes) or “filthy lucre” (preachers) but an objective esthetic value, a value rooted in the nature of how our minds work and in the need for incorruptible moral integrity. Why are wedding bands made of gold? Because gold is the symbol of remaining pure and true.

Gold jewelry is just as objective a value as utilitarian goods, such as bread or automobiles. But those goods provide value by being consumed—by being used up. You eat bread and it is gone. You drive a car and it wears out. Gold is almost unique in being an Unconsummable Consumable. Like Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover, gold provides value without being itself affected.

The oft-heard sneer, “You can’t eat gold” expresses a cynical materialism. Both artistic beauty and sensory beauty have their source in the nature of man as a conceptual being, a being who must use concepts and reasoning to survive and prosper. Animals cannot respond to artworks, or to the beauty of a brilliant sunset, or to the radiant, patterned purity of gold jewelry.

The objection “You can’t eat gold” confesses a mind-body dichotomy. In fact, material value requires spiritual value, and vice-versa. For man, “value” always involves a spiritual component. Even to value food, a man has to want to live—which takes an inner resolve to fight for his own happiness.

Gold is the ultimate expression of mind-body integration. It is denigrated as “crassly material” because it is beautiful—i.e., because gold is a spiritual value.

“You can’t eat gold” turns things upside down: gold is extra valuable because you can’t use it up. Gold as an Unconsummable Consumable does not have to be replenished. The gold jewelry of Ancient Egypt retains its value, bringing renewed pleasure to museum visitors daily. Because gold is, like a Rembrandt painting, an object of contemplation, it is used without being used up.

All this is why gold has monetary value. Because gold is of imperishable, objective value, it can serve as a store of value. And given that base (which bitcoin lacks), gold’s other inherent properties make it uniquely suited to serve as a medium of exchange. Unlike salt, gold has a high unit value. Unlike iron, gold does not rust. Unlike diamonds, gold can be easily divided into very small pieces without losing value. Unlike a computer chip, gold is homogeneous. And because it is ductile and malleable, gold can easily be fashioned into jewelry and gold leaf.

Salt and cigarettes have served as money, but their value rests upon their ultimately being consumed, which destroys them in the process. Gold can be used as money without ever being used up, without needing to be re-produced.

You don’t have to eat gold to get objective value from it. Beauty, though not material, is a rational, objective value, because its sensory beauty provides a spiritual pleasure.

Gold has esthetic value and—as men’s free choices demonstrate—monetary value. That is the power and the glory of gold.

It was in January of 2006 that Al Gore’s film, An Inconvenient Truth, was released. The film predicted looming climate disaster. What happened? Nothing.

This is what I don’t understand about the “common man.” He knows, or should know, that he has been told for either his whole life or the biggest part of it that monstrous, cataclysmic planetary disaster was looming. The drumbeat started in about 1969. Back then it was pollution and overpopulation, with a little climate hysteria on the side.

The cover of Newsweek, of January 26, 1970, featured a picture of Earth from space with arrows of destruction attacking it from all sides. The cover text was “The Ravaged Environment.” It contained a warning about climate change—both warming and a new ice age.

What happened? Well, some claim that the catastrophe has been pushed back a little by the measures we took. What measures? Well, recycling. And the Clean Air Act and the establishment of the EPA, they say.

But that doesn’t hold up at all. It’s impossible to believe that these trivial things in the United States change the monumental forces that were supposedly going to end life on this planet.

And how do people deal with the fact that, aside from the interminable back and forth in the scientific debate, everybody knows that nothing significant has happened to climate in the past 100 years?

I mean, who doesn’t know the following? Paris in 1922 had weather indistinguishable from Paris 2022. Same for Sydney, Buenos Aires, Miami, Los Angeles, Jakarta, Vienna, Oslo, Calgary, Bombay, Honolulu, Wellington, Juneau, Moscow, Santiago, Helsinki . . . you name it.

But, but, but . . . they sputter . . . what about the melting of the ice caps? What about rising sea levels?

I’m not going to cite scientific facts (though I’m sorely tempted to) but just ask: is there anywhere on any coastal city where sea-level rise over the last 100 years has been a problem? Have the low-lying streets of San Francisco, New York, Miami, etc., been flooded?

How about changes that affect anybody since Al Gore’s thundering “sky is falling” film? Nope. There must have been some changes somewhere that at least came to the attention of local residents. Someone on HBL said the growing season in his area has lengthened a bit. But where is the apocalypse?

If there had been a looming disaster 16 years ago (or 52 years ago), shouldn’t it be at least noticeable by now? Since it has not been noticeable, wouldn’t the rational thing to be now exhibiting increasing skepticism about climate disaster? Yet that’s not what we see.

Ayn Rand wrote,

| There is nothing so naïve as cynicism. A cynic is one who believes that men are innately depraved, that irrationality and cowardice are their basic characteristics, that fear is the most potent of human incentives—and, therefore, that the most practical method of dealing with men is to count on their stupidity, appeal to their knavery, and keep them in constant terror. | ||

The corollary is: there is nothing so practical and realistic as moral integrity. There is nothing so powerful as principled, uncompromising moral judgment.

That’s why the world’s unusually forceful condemnation of Putin’s murderous invasion of Ukraine may lead to his downfall. And why rather than emboldening Xi, the morally righteous damnation of the invasion seems already to be throwing Xi into retreat-mode.

The UN General Assembly voted overwhelmingly to condemn Putin’s invasion. More important were the condemnations from private American firms like Apple, Shell Oil, Boeing, ExxonMobil, and Netflix, to name a few.

Words speak louder than actions. This reversal of the traditional saying follows from the understanding that men’s actions are dictated by the ideas they hold. The traditional order—actions speak louder than words—is valid, but its application is to judging what ideas actually drive an individual. If he says, “We should do X” but secretly does Y instead, we know his actual belief is that Y is more important than X.

But on a national scale, what counts is not the judgment of any given person’s honesty and sincerity, but the evaluation of the actions and the identification of its premises.

No dictator can stay in power once he loses a moral sanction. If a man like Putin comes to be viewed as evil by the people he is trying to rule, he is lucky to elude the guillotine.

Monetary sanctions mean little. Moral sanction means everything. And I’m referring to moral judgment that is clear, rational, and convincing. That isn’t hard in the present case of a bloody, murdering, ex-KGB man who runs a giant slave pen.

On January 30, 2022, I interviewed Peter Schwartz about the publication of his book, The Tyranny of Need, his expanded version of In Defense of Selfishness:

Recently there’s been some discussion about the delegation of rights to the government, and some have expressed concern about the need to retain rights (especially the right to self-defense) rather than delegate them.

But that is a wrong notion of “delegation.” The meaning of “delegation” is the authorization of someone to act as your agent. Think of delegating a task to an employee. I’ve delegated the task of proofreading the posts, especially mine, to Stephanie Bond. In no way does that mean I have lost the right to proofread!

Likewise, when I delegate to the government my right of self-defense, I don’t lose that right.

Objection: But don’t you lose the right to apprehend and punish those who initiate force against you?

Answer: No, because I never had that right. In “the state of nature,” the state before government, it was moral, given certain circumstances, for a man to forcibly punish another, but it was never a right. You have no right to threaten another individual, but that’s what acting as your own judge, jury, and executor would be doing.

All that “delegating your rights to the government” means is: authorizing a third party (the government) to protect your rights more powerfully than you could and, crucially, to do so in a way that will not be threatening to others, because they will not have to guess at the motivation and reliability of some exponent of “frontier justice.”

You retain the rights that you delegate to the state.

As I said in another post, I recommend using New Year’s Eve as a time to review and write down your accomplishments over the year. When I did that, I realized that I wanted to take public note of the fact that in my OCON 2021 talk, I made a sizeable contribution to the cause of freedom.

My talk identified, defended, and applied what I believe to be a new point in political philosophy: all government regulation is wrong. The title of the talk was “All Regulation Is Over-Regulation”—playing off the lame conservative desire to “cut the red tape” and pare back “unnecessary regulations.”

You may object: “Wait, lots of people for a long time have said that government shouldn’t intervene in the economy.” Yes, but my talk was much wider than that. It didn’t cover just economic interventionism, and it defined the whole issue in terms of what is force, what is the threat of force, and what makes for an objective threat. Consequently, I see the same principle in far-flung issues: gun control, immigration control, building codes, food and drug regulations.

I stressed that evidence of potential harm has to be about specific individuals, drawing upon this passage in OPAR:

information about the capacities of a species is not evidence supporting a hypothesis about one of its members. From “Man is capable of murder” one cannot infer “Maybe Mr. X is the killer we are seeking.”

However, it was the following statement of hers that inspired me, and it was in my notes to quote in the talk, but somehow I overlooked it.I don’t think you can find anything in Ayn Rand dealing with all regulation, regulation per se, rather than just economic controls.

the legal hallmark of a dictatorship [is] preventive law–the concept that a man is guilty until he is proved innocent by the permissive rubber stamp of a commissar or a Gauleiter.

“Who Will Protect Us from our Protectors?” The Objectivist Newsletter, May 1962

Looking at issues from the standpoint of whether or not they constitute preventive law is immensely clarifying.

I will check on whether ARI is selling the recording of “All Regulation Is Over-Regulation.”

Is there any non-Objectivist commentator who is not a Peter Keating? Keating’s psychology is the only thing that can explain the insane view that cozying up to homicidal maniacs, such as the Chinese dictator, is going to “improve relations.”

I’ve been politically aware for over half a century, and throughout that time I’ve seen nothing but praise for “talks” and “summits” and “relaxing tensions” with the evil.

Actually, I can think of one man who understands the real situation. It is one of the Soviet dissidents, I think Natan Sharansky, but maybe it was Gary Kasparov, who tried to explain to American audiences that the policy decisions of Soviet leaders were motivated by a single need: to keep the populace from overthrowing them. He explained how the leaders live in constant fear of an uprising from the people whom they are victimizing.

But that is from a different universe than the one our Keating officials and Keating commentators inhabit. In their cosmos, smiles and frowns are the means of inducing others to produce the desired behavior.

Once President Xi comes to understand us and see that we have the same underlying concerns as . . . wait, he does understand us and that’s why he hates us.

The philosophical input to this understanding-means-peace approach and the (always refuted) belief that “quiet diplomacy” can work is Kant. He is the philosopher who “taught” us that formal structure and process are all that matter, that we deal only with appearances, never with what an entity is. His philosophy leads to ignoring the nature of the entities that act, so we don’t have to hold in mind that our co-summiteer is a murderous villain.

I posted the fascinating email exchange that a member had with a union organizer. One of the organizer’s claims commits a form of the equivocation between the dollar and the gun—i.e., between economic power and political power.

It has helped me to a deeper understanding of the equation of the dollar with the gun: it is the fallacy of regarding the values achieved by others as a threat to oneself.

When named that way, it sounds bizarre—except psychologically, where we do understand it. Psychologically, the envy-ridden loser fears and hates the achievements of others because those achieved values confront him with his own self-made failures.

Values as threats is the meaning of the union organizer’s claim that workers need collective bargaining to gain “bargaining power.” Otherwise the employer has all the bargaining power.

This kind of stuff works by cartoon thinking:

You can’t see there the face of the supplicating “little guy.” But we all know the image of “the downtrodden” from the movie of “Grapes of Wrath”:

The employer’s “power” is the power of the dollar, not the power of the gun. It is the power to offer payment. It’s the power to offer some of one’s achieved values in trade. It’s the power to pay you.

But what about “bargaining power”? Presumably, that’s a greater ability to dictate the terms of an exchange.

Logically, all trades are win-win.

Morally, there’s no principle concerned with comparing the wins of each party. The outcome of buyer gaining ten times what the seller gains is just as moral as the reverse. And rarely acknowledged is that everyone is both buyer and seller.

Economically, negotiations for business expenses such as wages and salaries are not governed by emotions (greed or pity), but by the facts (the worker’s contribution to production). But in the sticky spider web of Leftist economics behind the “bargaining power” conception, let me set the metaphysics right-side up.

If “bargaining power” means the ability to fine-tune the terms of the deal in one’s favor, then the poorer you are, the greater your bargaining power.

No, that’s not a typo. If we’re talking about an individual deal made between a rich person and a poor one, then dollar for dollar the poor man has greater power.

Why? It has to do with the proportionality of the value of a dollar.

To a billionaire, $1000 is essentially nothing. It’s one one-millionth of his wealth. That’s below his threshold of even thinking about (see my post on thresholds).

To a person of middle income, $1000 is a figure to be reckoned with. It is maybe a week’s income.

To a penniless immigrant, $1000 is everything.

So you want to trade with people much, much richer than you. The poorer person has an advantage: amounts of money that are big to him are small to the wealthy—and the wealthier they are, the smaller that amount of money is to them.

Everyone knows this on some level. If you want to sell your services as a chauffer, are you more likely to be hired by someone as poor as you or someone wealthy? And if you are hired, is it more in your financial interest to work for the comfortably wealthy or for the super-rich?

The less wealth you have compared to your potential trading partner, the more bargaining power you have.

The values possessed by others are what they have to pay you with. The more they have, the better for you. Out of sheer, naked greed, you should wish everyone to get rich. You should want them to have so many cars, yachts, homes, computers, and rockets to space that they wouldn’t at all mind giving one or two to you.

Remember the old expression, “He’d give you the shirt off his back”? That was from a time when you couldn’t just call an Uber to take you to a nearby Walmart to buy a replacement shirt for $15. What made the difference? We’ve got more stuff—and more ability to make still more stuff. All of us have a whole lot more wealth.

The fact that others have earned a lot of values is immensely valuable to you.

Back to the union organizer on a different aspect: the issue of individual, one-to-one hiring vs. collective bargaining.

Collective bargaining decreases your bargaining power.

If you are negotiating one-to-one with someone hiring you, you can ask for more than the average. If your ability is above average, you’ll probably get it. But if the employer has to deal with all of his employees as a block, you can’t get more than the average.

This supplies the answer to a question that puzzled me about this passage in Atlas:

| “We all have the same problems, the same interests, the same enemies. We waste our energy fighting one another, instead of presenting a common front to the world. We can all grow and prosper together, if we pool our efforts.” “Against whom is this Alliance being organized?” a skeptic had asked. The answer had been: “Why, it’s not ‘aga inst’ anybody. But if you want to put it that way, why, it’s against shippers or supply manufacturers or anyone who might try to take advantage of us. Against whom is any union organized?”

“That’s what I wonder about,” the skeptic had said. |

||

For many decades I couldn’t figure out against whom unions are organized. Now I see the answer: collective bargaining is aimed at those with higher-than-average ability. If the aim is to force the employer to pay one wage rate for everyone having the same “seniority,” then the employer can’t discriminate on the basis of productiveness.

This means the more productive are forced to subsidize the less productive.

Of course, some unions don’t operate that way. And all unions do some things, however sporadic and meager, to provide real benefits to all that are not a part of the aforementioned “leveling.” Those things don’t change the fact that collective bargaining reduces the rewards for those with greater productive ability.

Not only is that disgustingly unjust, it holds back the rise in living standards across the economy.

So you see that underneath the simple claim that workers need to organize in order to pose a counterforce to the huge bargaining power of the fat cats, there is an entire, inverted, irrational philosophy.

My work on the philosophy of mathematics has sparked a recognition of a new epistemological-ethical principle: establishing thresholds is essential to success in thought and action.

A “threshold” is a lower bound of significance–a degree below which something has too little cognitive or existential impact to be entertained.

For instance, your chance of buying a winning lottery ticket or of getting hit by falling space debris is sub-threshold, so you should take no action based on that and give it no thought (beyond the judgment that these events are sub-threshold).

This supplements the Objectivist understanding of the arbitrary. The arbitrary has no evidence and is asserted on the premise of “evidence—who needs it?!” Entertaining the arbitrary is treating imagination as if it were cognition.

But the sub-threshold is different. “You have a 1 in 12 million chance of winning this lottery” is put forward on the basis of mathematics, not emotion. One could argue that by implication acting on this mathematics is emotionalist, but that presupposes the point about thresholds that I’m going to make: to grant significance to things with too little evidence or too little value is to engage in context dropping.

What context is dropped? The context of all the other things that have, in the mathematical sense, a 1 in 12 million chance of happening. There’s a a much better chance (1 in 2.6 million) chance of being dealt a royal straight flush in poker, so before one buys that lottery ticket one would have to consider betting the limit, sight unseen, on the next poker hand. There’s no doubt at least a 1 in 12 million chance that while you are in the store to buy the lottery ticket, an armed robber will enter and you will get shot. There’s a 1 in 12 million chance that you will receive a fortune in the near future in some other way. There’s a 1 in 12 million chance you will be struck by lightning, that building you are in will collapse, that a talent scout will decide you are have just the right look for a certain role in the next blockbuster movie. Etc.

There are far too many things to think about and do if all sub-threshold chances are to be taken as significant. And in practice what happens is that whatever fantastically unlikely scenario is talked up becomes the one that is treated as if it were the only one.

Many people are impressed, for instance, with the thousands of cases of, alleged or real, bad reactions to the Covid vaccines. But they have forget that one thousand bad outcomes out of one billion vaccinations is one in a million. And they drop the context of the greater than one in a million chance of experiencing severe medical problems from being unvaccinated and contracting Covid.

Thresholds are contextual. A very slight chance of getting a cold is, for most people, negligible. The same chance of dying is quite significant. At the end of We the Living, we see Kira taking a high degree of risk trying to escape Soviet Russia, because the alternative was unthinkable.

It is important, therefore, to determine whether a given degree of evidence (and when to count statistics as evidence) or a given degree of value or disvalue is entitled to one’s attention.

In mathematics, I promote the concept of “nil,” which is a magnitude that isn’t zero but is too small to detect or too small to matter—to matter in application.

For instance, in measuring rugs for your home, the threshold length may be a half foot, it may be an inch, it could even be an eighth of an inch. But it cannot be a millionth of an inch. But in measuring the size of molecules that can cross a given cell membrane, a millionth of an inch may make all the difference.

There’s the flip side of “too small too matter”: so big that increases don’t matter. This is the rational meaning of “infinity” in one sense of that term. Something is infinitely big if additions to it make no difference. (In effect, for any n, ∞+n — ∞ = nil.)

It is good to apply thresholds to establish what’s “enough.” Perfectionism is precisely the error of dropping the context and thinking any improvement, no matter how small, is significant. For the perfectionist, infinity is never reached; his work is never good enough, because there’s always more polishing of it that can be done. (As an advocate of contextual perfection, I must add that the charge of “perfectionism” is often hurled at those who simply demand more of themselves and others than the accuser wishes they did.)

Perfectionism is the same issue as thinking one “just might” win the lottery: it’s failing to consider what the operative threshold of significance implies as to other things. Yes, by spending more time editing this post, I could add some to its value; but what are the other things I could be using that time for? Yes, by working an extra hour longer a billionaire probably can make an extra $1,000 dollars. But what else could he be expending that hour on? Are the selfish rewards of increasing his wealth from $1,000,000,000 to $1,000,001,000 greater than the selfish rewards of dinner with friends? Improving his tennis game? Thinking about a philosophic topic, such as the need to set thresholds?

The point is not what answer one gives to those judgments; the point is the need to face these issues consciously and deal with them rationally.

Note that overconcern with the threshold being “exactly” right is itself a violation of the threshold principle. In the region of the threshold, small differences are way sub-threshold. Suppose our billionaire is trying to set a monetary threshold for what amount of money begins to matter to him. Suppose his estimate is: $1,000. Anything below that is, to him, what less than a penny is to us. But then he wonders: “Maybe my threshold should be $1200 per hour. But $200 has to be nil to him. The difference for him between a threshold of $1,000 and $1200 isn’t, for him, worth worrying about. It would be like, for us, worrying about the difference between a penny and 1.2 pennies.

So, thresholds are normally approximate, because differences close to the threshold make no difference.

Between “nothing’s there” and “something’s there, what do I do about it?” there is a third condition: “something is there, but it’s too little to devote any of my scarcest resource—time—to thinking about or dealing with.”

Belief in something without evidence is invalid. It leads to total skepticism, which in turn opens the door to mysticism (if nothing can be known for certain, you are “free” to indulge in whatever nonsense you like).

Doubt of something for which there is conclusive evidence is also arbitrary. “I have no counterevidence, but just maybe . . .” is fully as wrong as “I have no evidence, but just maybe . . .”

Let’s apply this to Covid vaccines. I will limit it to the mRNA vaccines of Moderna and Pfizer because I know most about them and they are the most commonly used ones (at least in my survey of HBLers).

The safety and efficacy of the mRNA Covid vaccines are established beyond any reasonable doubt. Remaining doubts are either uninformed or unreasonable. Here are some of the facts that make up the conclusive evidence.

1. The mRNA vaccines are known to be safe, from our understanding of how they work biochemically, how they performed in the clinical tests on 50,000 people, and what has happened to the more than 100 million Americans who have been fully vaccinated with them, which means 200 million shots administered.

What have been the bad results? [Sound of crickets.]

If you inject anything, even a saline solution, into 100 million people, there will be a few subsequent (not necessarily consequent) bad experiences. How many have there been to the mRNA vaccines? I don’t know, but it can’t be many or it would be all over Fox News.

Let’s say that there have been 1000 non-transitory bad results, which we could say are possibly caused by the vaccine. That means a random person in the U.S. has a 1 in 100,000 chance of a bad result. Can there be a rational worry about facing those odds? No.

2. Your doctor, I bet, wants you to get the vaccine. Dr. Amesh Adalja, the Objectivist infectious disease specialist, is strongly pro-vaccine.

3. 637,000 Americans have died from Covid, so if we do the same kind of individual-blind statistics I did in step (1), we get your chance of dying from Covid as 1 in 1900 (vs. not death but some kind of serious trouble with the vaccine for 1 in 100,000). Yes, you can say this kind of raw division of numbers doesn’t take account of individual differences, but that doesn’t help: healthy, vigorous, young people will do better with the shots just as they will do better in not dying from Covid.

4. Are there long-term effects of mRNA that will show up years later? No, it does not get inside the cell nucleus and it degrades quickly.

Facts about COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines

They cannot give someone COVID-19.

–mRNA vaccines do not use the live virus that causes COVID-19.

They do not affect or interact with our DNA in any way.

–mRNA never enters the nucleus of the cell, which is where our DNA (genetic material) is kept.

–The cell breaks down and gets rid of the mRNA soon after it is finished using the instructions.

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/mrna.html

Now that is from the CDC, but it’s not contested or controversial.

5. The CEOs of both Pfizer and Moderna got shots of their own vaccines. This by itself is strong evidence of safety. It’s impossible to think that a layman following internet chatter knows as much about these vaccines as the CEOs of Moderna and Pfizer.

Here are a couple more facts to consider from the University of Alabama website, beginning with a statement by the director of the Alabama Vaccine Research Clinic at the University of Alabama at Birmingham

“Many people worry that these vaccines were ‘rushed’ into use and still do not have full FDA approval — they are currently being distributed under Emergency Use Authorizations,” Goepfert said. “But because we have had so many people vaccinated, we actually have far more safety data than we have had for any other vaccine, and these COVID vaccines have an incredible safety track record. There should be confidence in that.”

Unlike many medications, which are taken daily, vaccines are generally one-and-done. Medicines you take every day can cause side effects that reveal themselves over time, including long-term problems as levels of the drug build up in the body over months and years.

“Vaccines are just designed to deliver a payload and then are quickly eliminated by the body,” Goepfert said. “This is particularly true of the mRNA vaccines. mRNA degrades incredibly rapidly. You wouldn’t expect any of these vaccines to have any long-term side effects. And in fact, this has never occurred with any vaccine.”

https://www.uab.edu/news/health/item/12143-three-things-to-know-about-the-long-term-side-effects-of-covid-vaccines

This adds up to a case as strong as the case against OJ Simpson. Maintaining, in the face of that evidence, that the vaccines are unsafe is like maintaining there wasn’t enough evidence to convict Simpson.

Is it a good strategy to be avoid confrontation in arguing for Objectivist ideas, so as not to set off your discussant’s defenses?

You can’t answer that question as stated. First, make this crucial distinction: ideas vs. people.

In criticizing ideas, such as altruism, you need to be forceful and call a spade a spade. This includes being clear and objective: defining altruism in terms of self-sacrifice, duty, etc., and giving reasons for your conclusion.

In other words, you would not in conversation or to an audience or in writing say something like, “Altruism’s not my cup of tea.” No, you would make such points that altruism means the surrender of your values for the benefit of anyone who is non-you, that altruism has been the justification for every modern dictatorship, that full sacrifice of your values means your death. You would point out that there has been no argument ever given as to why we should sacrifice.

That’s being “confrontational” in regard to the idea of altruism. But it would be wrong to attack the person you are talking to: “You are an altruist and therefore are on the death premise.”

If you regard the person or people that you are talking to as evaders, as seriously immoral, then you should not be talking to them.

Conversely, if you are talking to them, it has to be on the premise that they respect rational arguments and that you share some starting point with them.

It’s neither practical nor morally proper to discuss ideas with those who reject reason.

So, it’s a mistake to think you have to be “non-confrontational” in discussing your ideas. That’s coming at it from the wrong perspective. You should give reasons for true, positive ideas and condemn and invalidate the wrong ideas. But your discussant or your audience has to be taken as open to reason and sharing with you some rational values if you are going to have or continue a discussion of ideas with them.

Confront the ideas not your audience.

The following is reprinted from the “Q & A Department” of The Objectivist Forum, December 1981. It was inspired by a private discussion with Ayn Rand on this issue. Subsequently, she read this piece and expressed no disagreement with any of it.—Harry Binswanger

Q: Does the law of identity imply that at every instant in time a moving object must be located at a definite point in space?

A: No. The law of identity implies that there are no such things as “instants in time” or “points in space”—not in the sense assumed in the question.

Every unit of length, no matter how small, has some specific extension; every unit of time, no matter how small, has some specific duration. The idea of an infinitely small amount of length or temporal duration has validity only as a mathematical device useful for making certain calculations, not as a description of components of reality. Reality does not contain either points or instants (in the mathematical sense).

By analogy: the average family has 2.2 children, but no actual family has 2.2 children: the “average family” exists only as a mathematical device.

Now consider the manner in which the question ignores the context and meaning of the concepts of “location” and “identity.”

The concept of “location” arises in the context of entities which are at rest relative to each other. A thing’s location is the place where it is situated. But a moving object is not at any one place—it is in motion. One can locate a moving object only in the sense of specifying the location of the larger fixed region through which it is moving during a given period of time.

For instance: “Between 4:00 and 4:05 p.m., the car was moving through New York City.” One can narrow down the time period and, correspondingly, the region: but one cannot narrow down the time to nothing in the contradictory attempt to locate the moving car at a single, fixed position. If it is moving, it is not at a fixed position.

The law of identity does not attempt to freeze reality. Change exists: it is a fact of reality. When a thing is changing, that is what it is doing, that is its identity for that period. What is still is still. What is in process is in process. A is A.

Unless some of the mutant strains are able to elude many of the vaccines—which I doubt—the pandemic is over.

New cases have plunged to one third of their peak value. The 7-day moving average was as high as 255,000 new cases and is now (February 16th) about 82,000. This is not well reported, because “Things are returning to normal” is like “Dog bites man.”

So, now is a good time to look back and assess what happened.

This was a nature-made disaster. But its harm was so magnified by government that one has to view the bulk of the suffering and deaths as due to disastrous government policy.

Above all, responsibility for the destruction has to be assigned to the FDA.

There are five levels here.

Level 1. The FDA as such

Had there been no FDA for the last 50 or 100 years, it is beyond question that medicine would have been so radically advanced that no virus could have created a pandemic. One factor accelerating medical progress would, of course, be the elimination of the years or decade of time wasted waiting for bureaucrats to permit offering medications on the market.

But the much more potent accelerator would be the Big Data doctors and researchers would get if the public were permitted to ingest whatever they wanted to. A huge pool of mini-experiments like that gives rise to quantum leaps of progress.

If a government bureau, like the FDA, wants to issue recommendations, that’s one thing. But it’s something else entirely when they seek to gain control over your health decisions. By what right, and at what cost, does a government agency stop you by force from taking the medication you think best?

And it is force: government is the agency whose rulings are mandatory, being enforced by the police. Government is the social institution in charge of the use of physical force within its territory. Laws are not suggestions or recommendations.

No individual has the right to use force to stop you from taking a medication, and neither do 100 million individuals, and neither do the politicians who appoint the panel of experts. Your life is your own, your mind is your own, your body is your own.

Using the police power of the state to enforce even a distinguished panel’s conclusions about personal health is totally improper and destructive. Placing science under political control can only lead to the corruption of science and to popular distrust, as we have seen in regard to the vaccines.

Level 2. The FDA on efficacy

As of mid-February, 1000 times more Americans than were in the clinical trials have received both doses of the Moderna or Pfizer vaccine. Had Moderna and Pfizer been permitted to sell their vaccines while clinical trials were being conducted, the vaccination process that began in December would have begun in May. Those additional six months cost many thousands of lives. And scientists would have tens of millions of informal data points to consider.

Note: the Phase III trials were not for safety but for efficacy. The government was satisfied on the safety of Moderna’s vaccine (reference) after the Phase I trials of March through early May. (The company then looked at efficacy for its own information and found that every single one of the 45 subjects developed high levels of antibodies to the coronavirus by two weeks after getting their second dose.)

Your right to act on your own conclusions about your health was taken away by 1962 legislation expanding the FDA’s role to cover not just the safety but also the effectiveness of medicines and medical treatments. That was an immoral and deadly enlargement of state power over the individual. The premise was paternalism: “We experts won’t permit people to waste their time and money on things that, even if safe, don’t work.” It doesn’t matter whether the experts do know better or are an ossified establishment: decisions regarding your health are yours to make.

Back near the beginning of this nightmare, The Wall Street Journal published an op-ed pleading for the FDA, in this emergency, to drop the efficacy requirement and revert to the pre-1962 standard: safety. Tragically, the plea was completely ignored.

Level 3. The panic over hospital overcrowding

The public and politicians alike over-reacted to the possibility that hospitals could be temporarily unequipped to deal with a surge in Covid cases. In the ensuing hysteria, the country was locked down for month after month, businesses were bankrupted, jobs were lost, people’s lives were shaken, and there was a massive loss of wealth—all to prevent hospitals from being unable to handle all the Covid cases.

Why is shutting down the whole country preferable to hospitals not having enough staff or beds for all the Covid sufferers? The answer is: the tragedy at the hospitals is visualizable in contrast to the less easily visualized but even-greater tragedies resulting from extended shutdowns of the economy.

Plus, the ethics of altruist self-abnegation made intolerable the prospect of doctors having to decide whom to treat and whom to crowd out. “We can’t have some doctor or his staff deciding who will live and who will die.” (Why not? No answer.)

The absolute was: hospitals must not be overloaded. That would have made sense if mass vaccination had been just a week or two away. Then you could have argued that the government would accomplish something in its desire to “Flatten the curve” But the FDA made sure that the vaccines would not be released until “adequate testing” had been conducted, written up, forms filled out, and ruled upon by faceless bureaucrats. So the effect of all the lockdowns and general havoc the government wreaked was merely to add a slight delay to what was inevitable: the spread of the virus through the unvaccinated population.

Level 4. Capitalism non, socialism sí

Right from the beginning, the responsibility for everything having to do with the pandemic was taken away from individuals and made into a collective—i.e. governmental—responsibility. Even the military was involved in what should have been business activity on a free market. Never considered was the free-market solution: profit. The selfish search for profits would have resulted in many resources being pressed into service, and their owners highly rewarded, which is what justice demands.

We needn’t have strangled everyone with “flatten the curve” lockdowns. We needn’t have let the bureaucracy go power-mad. Instead, the same quest for profit that fills the supermarkets and clothing stores could have turned that hospital capacity line sharply upward, instead of destroying the economy for the sake of spreading out the same number of cases over a longer time frame.

As I wrote back then, why not pay physicians and health staff ten times the normal rate to attract out-of-state and out-of-country physicians, nurses, and hospital personnel? During the February crisis in New York City, it would have been much cheaper to offer out-of-state doctors $1 million per week to come to NYC to help with the crush.

Regarding distribution of the vaccines, the free market would have speedily and efficiently gotten the vaccines from the lab into production and into people’s arms. Businesses pursuing high profits do not exhibit the incredible bungling we’ve witnessed from government taking over distribution and injection of the vaccines.

Level 5. The FDA and testing

All that I have said about how government coercion prevents us from getting vaccines applies just as much to government coercion preventing fast and accurate testing from being made available. Often during the last year, we heard about newly developed fast, easy, at-home testing. But it never seemed to materialize. The cause: government paternalism, prohibitions, and the government’s disastrous tort law system, which make it almost impossible to sell any medical product. Just this morning, the WSJ’s story was headlined: “Rapid Covid-19 Tests Go Unused”:

The U.S. government distributed millions of fast-acting tests for diagnosing coronavirus infections at the end of last year to help tamp down outbreaks in nursing homes and prisons and allow schools to reopen.

But some states haven’t used many of the tests, due to logistical hurdles [that for-profit companies seem always to surmount] and accuracy concerns, squandering a valuable tool for managing the pandemic. The first batches, shipped to states in September are approaching their six-month expiration dates.

Bear in mind that the Moderna vaccine was created in a couple of days back in February 2020. There is no scientific problem in devising a vaccine effective against the coronavirus. The problems are political, which means ideological, which means philosophical. For two centuries the philosophy of self-abnegation and coerced submission to the collective has been replacing the original American philosophy of reason, self-interest, and individualism. The predictable calamity was in fact predicted by Ayn Rand through the hero of Atlas Shrugged, who says, in a different situation:

It was man’s mind that all their schemes and systems were intended to despoil and destroy. Now choose to perish or to learn that the anti-mind is the anti-life.

Nature produced the virus. The philosophers and intellectuals preached the collectivism that barred free individuals—patients, doctors, researchers, pharma companies—from taking rational action to defeat it.

The notion of “white privilege” is collectivist. It’s Marxism seen through a racial lens.